Photoemission spectroscopy

Photoemission spectroscopy (PES), also known as photoelectron spectroscopy,[1] refers to energy measurement of electrons emitted from solids, gases or liquids by the photoelectric effect, in order to determine the binding energies of electrons in a substance. The term refers to various techniques, depending on whether the ionization energy is provided by an X-ray photon, an EUV photon, or an ultraviolet photon. Regardless of the incident photon beam however, all photoelectron spectroscopy revolves around the general theme of surface analysis by measuring the ejected electrons.[2]

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was developed by Kai Siegbahn starting in 1957 [3][4] and is used to study the energy levels of atomic core electrons, primarily in solids. Siegbahn referred to the technique as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), since the core levels have small chemical shifts depending on the chemical environment of the atom which is ionized, allowing chemical structure to be determined. Siegbahn was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1981 for this work. XPS is sometimes referred to as PESIS (photoelectron spectroscopy for inner shells) whereas the lower energy radiation of uv-light is referred to as PESOS (outer shells) because it cannot excite core electrons.[5]

In the ultraviolet region, the method is usually referred to as photoelectron spectroscopy for the study of gases, and photoemission spectroscopy for solid surfaces.

Ultra-violet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) is used to study valence energy levels and chemical bonding; especially the bonding character of molecular orbitals. The method was developed originally for gas-phase molecules in 1962 by David W. Turner,[6] and other early workers included David C.Frost, J.H.D. Eland and K. Kimura. Later, Richard Smalley modified the technique and used a UV laser to excite the sample, in order to measure the binding energy of electrons in gaseous molecular clusters.

Extreme ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (EUPS) lies in between XPS and UPS. It is typically used to assess the valence band structure.[7] Compared to XPS it gives better energy resolution, and compared to UPS the ejected electrons are faster, resulting in a better spectrum signal.

Contents |

Physical principle

The physics behind the PES technique is an application of the photoelectric effect. The sample is exposed to a beam of UV or XUV light inducing photoelectric ionization. The energies of the emitted photoelectrons are characteristic of their original electronic states, and depend also on vibrational state and rotational level. For solids, photoelectrons can escape only from a depth on the order of nanometers, so that it is the surface layer which is analyzed.

Because of the high frequency of the light, and the substantial charge and energy of emitted electrons, photoemission is one of the most sensitive and accurate techniques for measuring the energies and shapes of electronic states and molecular and atomic orbitals. Photoemission is also among the most sensitive methods of detecting substances in trace concentrations, provided the sample is compatible with ultra-high vacuum and the analyte can be distinguished from background.

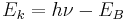

Typical PES (UPS) instruments use helium gas sources of UV light, with photon energy up to 52 eV (corresponding to wavelength 23.7 nm). The photoelectrons that actually escaped into the vacuum are collected, energy resolved, slightly retarded and counted, which results in a spectrum of electron intensity as a function of the measured kinetic energy. Because binding energy values are more readily applied and understood, the kinetic energy values, which are source dependent, are converted into binding energy values, which are source independent. This is achieved by applying Einstein's relation  . The

. The  term of this equation is due to the energy (frequency) of the UV light that bombards the sample. Photoemission spectra are also measured using synchrotron radiation sources.

term of this equation is due to the energy (frequency) of the UV light that bombards the sample. Photoemission spectra are also measured using synchrotron radiation sources.

The binding energies of the measured electrons are characteristic of the chemical structure and molecular bonding of the material. By adding a source monochromator and increasing the energy resolution of the electron analyzer, peaks appear with full width at half maximum (FWHM) less than 5–8 meV.

See also

- Angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy AR-PES

- Inverse photoemission spectroscopy IPS

- Ultra high vacuum UHV

- X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy XPS

References

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "photoelectron spectroscopy (PES)".

- ^ Hercules, D. M.; Hercules, S.H. Al (1984). "Analytical chemistry of surfaces. Part I. General aspects". Journal of Chemical Education 61 (5): 402. Bibcode 1984JChEd..61..402H. doi:10.1021/ed061p402.

- ^ Nordling, Carl; Sokolowski, Evelyn; Siegbahn, Kai (1957). "Precision Method for Obtaining Absolute Values of Atomic Binding Energies". Physical Review 105 (5): 1676. Bibcode 1957PhRv..105.1676N. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.105.1676.

- ^ Sokolowski E., Nordling C., Siegbahn K. (1957). Ark. Fysik. 12: 301.

- ^ Ghosh, P.K. (1983). Introduction to Photoelectron Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-06427-0.

- ^ Turner, D. W.; Jobory, M. I. Al (1962). "Determination of Ionization Potentials by Photoelectron Energy Measurement". The Journal of Chemical Physics 37 (12): 3007. Bibcode 1962JChPh..37.3007T. doi:10.1063/1.1733134.

- ^ Bauer, M.; Lei, C.; Read, K.; Tobey, R.; Gland, J.; Murnane, M.; Kapteyn, H. (2001). "Direct Observation of Surface Chemistry Using Ultrafast Soft-X-Ray Pulses". Physical Review Letters 87 (2): 025501. Bibcode 2001PhRvL..87b5501B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.025501. http://www.physik.uni-kl.de/aeschlimann/pdf/paper_00000012.pdf.

External links

- Presentation on principle of ARPES